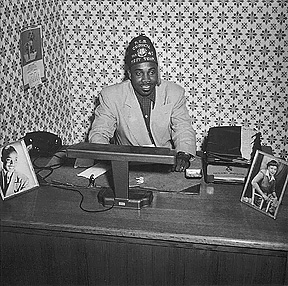

Gatemouth Moore

Last of the Great Blues Shouters

Listen to Gatemouth Moore on "I Ain't Mad at You, Pretty Baby"

What can be said about the only survivor of the Natchez, Mississippi night club fire that claimed hundreds of lives and was immortalized by Howlin' Wolf in the song "Natchez Burning?" Not a whole hell of a lot. As for what Gatemouth Moore says about it, "The only reason I survived, was because I was outside, in the bus, with a girl." The rest of his band, Memphis's Walter Barnes and the Creoles, perished in the fire.

Moore, presumably the last surviving member of F.L. Wolcott's Rabbit Foot Minstrels (the troupe that also employed the late Rufus Thomas) is 88 years young and one of the last of the great blues shouters. Gatemouth is the real deal, right along the same lines as his old running buddies Wynonie Harris and Roy Brown.

Following the Natchez fire, Moore cut his first record, and the one he would forever come to be associated with, "I Ain't Mad At You." "I was in Washington, D.C., when I wrote that one," Moore recalled to Aaron Fuchs, "A woman had just taken her shoe off and busted her old man across the head with it. As the cop car came to take her away, the guy ran up behind it, blood still running from his forehead, yelling, 'I ain't mad at you, baby!'"

In the late '40s, after cutting a string of records for National and King -- including the extremely influential "Have You Ever Loved A Woman"-Moore found himself experiencing a spiritual conversion onstage at a Chicago blues club, when he opened his mouth to belt the blues and inexplicably began singing the gospel classic "Shine On Me." He soon became a DJ at Memphis' WDIA, where he influenced a young Riley 'Blues Boy' King, and still later, was employed as a television reporter in Alabama, covering the civil rights movement firsthand.

As a revivalist preacher, Moore's greatest moment was perhaps the time he preached from a casket on Easter Sunday, cleared $38,000 and made such a spectacle of the whole thing ("The flowers, casket, the pallbearers and me in my red convertible. Took the casket out of the hearse and had the pallbearers carry the casket with all the money inside the bank") that an unappreciative sheriff gave him 24 hours to get out of town. He did so, only to return to Chicago, where he was made a bishop.

As a revivalist preacher, Moore's greatest moment was perhaps the time he preached from a casket on Easter Sunday, cleared $38,000 and made such a spectacle of the whole thing ("The flowers, casket, the pallbearers and me in my red convertible. Took the casket out of the hearse and had the pallbearers carry the casket with all the money inside the bank") that an unappreciative sheriff gave him 24 hours to get out of town. He did so, only to return to Chicago, where he was made a bishop.

Not surprisingly, Moore doesn't share the traditional view that blues and gospel cannot co-exist side by side. The difference, he states, is one thing: lyrics. The man is serious about his music, if an article he wrote in 1942 characterizing the Memphis scene can be taken as any kind of indication. In it, he's quoted thusly:

"The musicians don't take music as an art or a great profession. To them it is more a job or a livelihood. The boys don't dress like musicians. They are not outstanding in their profession because they don't have it in their heart. Good musicians are born and not made and it takes more than a musical foundation to establish good music from one. I wish the cats would wake up and think the situation over seriously."

We can only hope that Gatemouth will one day pen a similarly-themed article on the present day state of affairs in the music business. Now, that would be one article worth its weight in gold!

Listen to Gatemouth Moore on "I Ain't Mad at You, Pretty Baby"

What can be said about the only survivor of the Natchez, Mississippi night club fire that claimed hundreds of lives and was immortalized by Howlin' Wolf in the song "Natchez Burning?" Not a whole hell of a lot. As for what Gatemouth Moore says about it, "The only reason I survived, was because I was outside, in the bus, with a girl." The rest of his band, Memphis's Walter Barnes and the Creoles, perished in the fire.

Moore, presumably the last surviving member of F.L. Wolcott's Rabbit Foot Minstrels (the troupe that also employed the late Rufus Thomas) is 88 years young and one of the last of the great blues shouters. Gatemouth is the real deal, right along the same lines as his old running buddies Wynonie Harris and Roy Brown.

Following the Natchez fire, Moore cut his first record, and the one he would forever come to be associated with, "I Ain't Mad At You." "I was in Washington, D.C., when I wrote that one," Moore recalled to Aaron Fuchs, "A woman had just taken her shoe off and busted her old man across the head with it. As the cop car came to take her away, the guy ran up behind it, blood still running from his forehead, yelling, 'I ain't mad at you, baby!'"

In the late '40s, after cutting a string of records for National and King -- including the extremely influential "Have You Ever Loved A Woman"-Moore found himself experiencing a spiritual conversion onstage at a Chicago blues club, when he opened his mouth to belt the blues and inexplicably began singing the gospel classic "Shine On Me." He soon became a DJ at Memphis' WDIA, where he influenced a young Riley 'Blues Boy' King, and still later, was employed as a television reporter in Alabama, covering the civil rights movement firsthand.

As a revivalist preacher, Moore's greatest moment was perhaps the time he preached from a casket on Easter Sunday, cleared $38,000 and made such a spectacle of the whole thing ("The flowers, casket, the pallbearers and me in my red convertible. Took the casket out of the hearse and had the pallbearers carry the casket with all the money inside the bank") that an unappreciative sheriff gave him 24 hours to get out of town. He did so, only to return to Chicago, where he was made a bishop.

As a revivalist preacher, Moore's greatest moment was perhaps the time he preached from a casket on Easter Sunday, cleared $38,000 and made such a spectacle of the whole thing ("The flowers, casket, the pallbearers and me in my red convertible. Took the casket out of the hearse and had the pallbearers carry the casket with all the money inside the bank") that an unappreciative sheriff gave him 24 hours to get out of town. He did so, only to return to Chicago, where he was made a bishop.Not surprisingly, Moore doesn't share the traditional view that blues and gospel cannot co-exist side by side. The difference, he states, is one thing: lyrics. The man is serious about his music, if an article he wrote in 1942 characterizing the Memphis scene can be taken as any kind of indication. In it, he's quoted thusly:

"The musicians don't take music as an art or a great profession. To them it is more a job or a livelihood. The boys don't dress like musicians. They are not outstanding in their profession because they don't have it in their heart. Good musicians are born and not made and it takes more than a musical foundation to establish good music from one. I wish the cats would wake up and think the situation over seriously."

We can only hope that Gatemouth will one day pen a similarly-themed article on the present day state of affairs in the music business. Now, that would be one article worth its weight in gold!